Mrs Murphy

-

Most of the Cambridge histories in Victorian times concern men – their business interests, leisure pursuits, transgressions and good works. Victorian women, on the other hand, are difficult to research.

Their roles were largely seen as supporting their husbands or male relatives. They are sometimes depicted as victims. This article is about a woman who took the lead in her own business affairs, dealt directly with men, and most certainly did not categorise herself as anyone’s victim. Her name was Mary Teresa Murphy.

You will be hard-pressed to find Mrs Murphy’s name in any history books on Cambridge. William Rout wrote an extensive history of Cambridge in the 1890s, and did not once mention her. Cambridge’s definitive history Plough of the Pakeha makes a single reference to her husband Patrick when his carpentry shop burned down, but does not refer to her as the owner of the premises. After her death, you may see the occasional reference to the estate of M T Murphy – a block of properties in central Cambridge between Empire, Victoria and Alpha Streets. But once those properties were sold, all references to her cease.

If, however, you search for her in court documents and news reports during her lifetime, you get insights into her life and character.

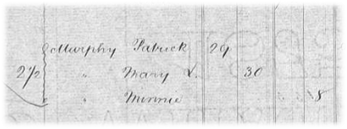

Passenger list entry on the ‘British Empire’

She was born Mary Teresa Cronin in Limerick, Ireland in 1844. Her father was a cattle dealer. At the age of 20, Mary married a local policeman named Terrence O’Connor, and they had a daughter Minnie (Mary Catherine). Ten years later, Mary married Patrick Desmond Murphy, a local carpenter. On 11 July 1875, Patrick, Mary and Minnie boarded the ‘British Empire’ and emigrated to Auckland.

The family settled in Cambridge. They would have been attracted by the economic boom Cambridge was experiencing as a notorious court town, hosting the hearings of the Native Land Court. People were arriving from all over the land to attend these hearings, and there was a sharp increase in flourishing businesses in Cambridge – especially in the hospitality industry.

Mrs Murphy, “a lady of proverbial enterprise”[1], purchased a house and premises between Alpha, Brewery (now Empire), and Victoria Streets, possibly with money left to her from her first marriage. The family occupied a house there, Patrick set up a carpenter’s workshop next door, and Mrs Murphy opened the Wharekai, a Maori restaurant, to cater for Māori who were accommodated in barracks hastily erected on the property where the Cambridge Town Hall now stands.

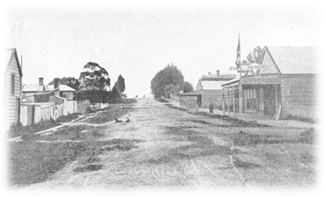

Brewery (now Empire) Street. Mrs Murphy’s properties can be seen at the far end of the street on the left –

now the site of the old Cambridge Electric Power Board building.

On 1 September 1881, we get our first glimpse of Mrs Murphy’s character as it appears in a Waikato Times article. She was charged with assaulting Mary Ann Teague by punching her and then striking her with a billhook, after accusing Mrs Teague of poisoning her fowls. Sergeant McGovern who conducted the prosecution said that Mrs Murphy, when drunk, was a perfect pest to the neighbourhood. Mrs Murphy defended herself by making a long statement on her good character which she said was well known to the police. Sergeant McGovern said the accused had better not go to him for a character reference.

Although the assault was shocking, no-one can deny the humour of the exchange in the courtroom between Mrs Murphy and Sergeant McGovern. This was an introduction to a long-running series of court appearances, in which Mrs Murphy was undoubtedly the star, with occasional support from husband Patrick. As time went by, more and more townsfolk attended her court hearings, knowing they were guaranteed a good show – with Mrs Murphy either the accused or the defendant. On several of these occasions, the public gallery was warned against excessive laughter.

Mrs Murphy’s Wharekai was popular, but short-lived. It had a tarred roof and a large oven inside. In 1882, it burned down in mysterious circumstances. Some thought it was arson; others believed that a fire was left burning in the back of neighbouring butcher Thomas Hoy’s premises; Hoy implied that the occupants of the Wharekai were “in no condition” to manage the heat from their large indoor oven.

In 1883, Patrick’s workshop also burned to the ground. Cambridge had no reliable water supply and therefore no Fire Brigade. Wooden buildings were vulnerable to fire and expensive to insure. The focus was to prevent the fire from spreading rather than trying to preserve buildings that were already alight. As money was plentiful in Cambridge at that time, neither of these setbacks seemed to affect the Murphys. Mrs Murphy was now 47 years old, Patrick 43, and Minnie 21[2].

Signature from Mrs Murphy’s will dated 1911

In the late 1880s, Cambridge suffered an economic downturn. Mrs Murphy lived off the rent from her properties and also ran a store, selling various goods such as fish, tobacco products, ginger ale, cakes, etc. She never missed an opportunity to make money, whether it was hiring out household furniture and fittings to her tenants or touting her wares in the street on Council meeting days. Every Sunday, she took her dinner at Hewitt’s at the Criterion Hotel. Men enjoyed her company and would often buy her drinks. Occasionally she lived alone when Patrick was sent off to Mt Eden jail to serve time for various drinking offences.

Her court appearances continued regularly for over thirty years. She died in 1913 of pneumonia at the age of 69 and was buried in the Hautapu cemetery. By then she had a fortune in Cambridge property and left her beneficiaries Patrick and Minnie weekly allowances. Patrick was allowed to live rent free in their Empire Street home until his death. Minnie would live off an allowance for 21 years and then inherit the properties.

Patrick did not cope well on his own. In his final years he was deaf, a chronic alcoholic and unable to look after himself. He had spent a year on Rotoroa Island – a Salvation Army-run rehabilitation facility for alcoholics, but relapsed almost immediately on return. When Sergeant Hastie suggested he be recommitted to the Island, Patrick threatened suicide, saying he would “never come out of it alive.” Patrick outlived his wife by five years, passing away on 22 June 1918 at around the age of 70. He is buried next to her in an unmarked grave.

Mrs Murphy’s daughter, Minnie

Minnie (Mary Catherine) Hoare nee O’Connor

The Auckland Star published the following birth notice on 30 August 1890: HOARE, – On August 17, at the residence of her mother, Mrs Murphy, Cambridge, the wife of Philip Hoare of a son; both doing well.

Mrs Murphy’s daughter Minnie Hoare’s story is a sad one. When their child was four years old, Minnie’s husband Philip Hoare died from suffocation, having fallen asleep with a coal fire next to his bed on board the cutter Tamaki Packet at Ngunguru. Although Mr Hoare bore a reputation in Auckland as a careful, steady man, he left his wife and son, also named Philip, destitute.

Fifteen years later, Minnie’s son Philip Hoare was charged with failing to provide for his mother. Philip, a gambler, had been fired from his job and owed his previous employer money. He was ordered to pay his mother 5/ a week and advised to find farm work. He refused to do so, and was sentenced to 14 days imprisonment. Although he was described as a “wild youth” in the press, his impoverished childhood and pressure to provide for his mother made his rebellion almost inevitable. He lived in Newton, Auckland, a place well on the way to earning a reputation as a “haunt of many of Auckland’s best-known crooks.” [NZ Truth 4/3/1926]

Philip Desmond Hoare died of tuberculosis aged 23 in Auckland Hospital, only a few weeks after the death of his grandmother. Mrs Murphy’s trustees had been searching unsuccessfully for 45-year-old Minnie, to fulfil the wishes of her mother’s will, and it was reported in the Waikato Times that they hoped to contact her at her son’s funeral. As her name is not recorded on Philip’s death certificate, they may not have done so. We cannot find any record of Minnie after 1909, and her disappearance remains a mystery.

[1] Waikato Times 1/1/1885

[2] Note that these ages are approximate. Various documents show different dates.

Written by Karen Payne for publication in the Cambridge Historical Society Newsletter June 2021