Te Miro – The Mill at Maungakawa

-

March 2020 marked the 100th anniversary of Te Miro School and District, although the Centennial celebrations planned in 2020 were delayed due to Covid-19. This article is on the early history of the Maungakawa Flour Mill.

The area was officially named Te Miro in 1916 when it was surveyed and developed for European settlement. Before that, it was shown as Maungakawa.

History

When the first settlers arrived in the North Island, Māori were able to supply them with pigs, potatoes, maize and wheat, all plants and animals left on the shores by European visitors from 1769 onwards. From around 1840, Māori were encouraged by Rev John Morgan of the Church Missionary Society to erect mills to expand their agriculture.

Sir George Grey was the first governor to encourage the development of Māori agriculture along European lines. He wrote to the Colonial Office in 1847 that when Māori were actively engaged in farming and owned quantities of produce, implements and mills, their property would “be too valuable to permit them to engage in war.”

Money was advanced by the Colonial Government to iwi to assist with the erection of mills. An Inspector of Native Mills was appointed in the early 1850s to assist in drawing up mill plans, supervise construction and give general assistance.

Lady Martin wrote of travelling in Te Awamutu countryside with her husband, the Chief Justice in 1852: “Our path lay across a wide plain, and our eyes were gladdened on all sides by the sights of peaceful industry. For miles we saw one great wheatfield. The blade was just showing a vivid green, and all along the way, on either side, were wild peach trees in full bloom. Carts were being driven to and from the mill by the Māori owners. The women sat under trees sewing their flour bags while fat, healthy children played around.”

Maungakawa mill construction

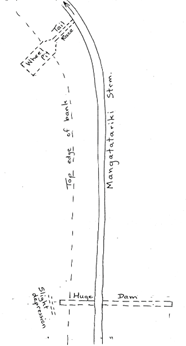

In 1852 the Maungakawa flour mill was built and soon in operation not far from the Māori settlement and what would later be the parliament building site.

Much labour by Māori was needed to make the wheel pit and dam. Around 136 cubic metres (4,800 cubic feet) of spoil had to be moved in flax baskets. Historian Arthur Moore estimated that it could have taken as many as 7,200 hours to complete.

The earthworks held back the neighbouring stream until enough water was collected to drive the undershot waterwheel and power the two scoria millstones, which were almost a metre wide. Millstones for a Maungatautari flourmill were from France and believed to have been ship ballasts. Maungakawa’s millstones may have had the same origin.

Trade

Native trade quickly sprang up with Auckland, flour-sack laden canoes travelling down the Waipa and Waikato rivers.

In 1852, the gold rushes in California and Australia forced up cereal prices. The value of wheat rose from five to fourteen shillings a bushel, stimulating Māori to plant increased acreage. However, when selling time came, the price dropped to just under five shillings per bushel. Māori, unused to the whims of supply and demand, refused to sell. Less was planted and much wheat seed deteriorated.

End of an era

The quality of the flour from the Maungakawa Mill was nearer to wheatmeal than to flour. While Auckland consumed relatively large quantities of the flour, only rarely was it exported overseas, because of its low quality. Top-grade European-ground flour always earned a higher market price.

Rev Ashwell wrote in 1856 that iwi were falling into debt, often before the mills and other agricultural implements and coasting vessels were fully paid for. The same seed was used year after year, instead of obtaining new stock.

With the decline of interest in agriculture in the Waikato in the late 1850s, mills fell into disrepair and the mill dams broke down. The era of Māori flour mills was past.

When the soldier settlers came to abandoned Maungakawa in 1919, the mill machinery was by the dam. They pushed it aside and covered it with soil.

Information for this article taken from Te Miro Centenary book; NZ Archaeological Association Site Record Form (pictured); The Māori Agriculture of the Auckland Province in the Mid-Nineteenth Century, Hargreaves; Auckland-Waikato Historical Journal No. 9, Moore; Plough of the Pakeha, Beer & Gascoigne. All in Cambridge Museum research collection.