Cambridge People

Explore the history of the generations of people who have shaped the Cambridge area.

Cambridge before the Fire Brigade

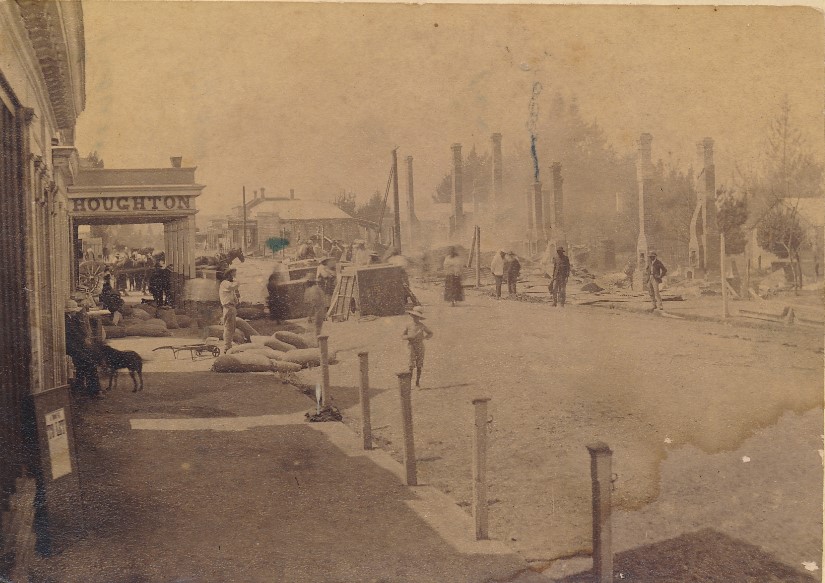

Most of Duke Street’s premises were destroyed by fire in 1889. Cambridge Museum 2958/9/37

“With wooden buildings and little or no water, the destruction to property could be enormous in a town like Cambridge. This is especially true in Duke Street, where stores and shops are close together,” prophesied Thomas Wells at a meeting in the Cambridge Public Hall in 1879.

The fifty to sixty people present immediately voted for the formation of a Fire Brigade of 20 officers, and for the supply of eight iron buckets and a hand engine.

However, they soon learned that a Fire Brigade could not be formed as Cambridge lacked a ready supply of water.

Arson and the night watchman

Between 1881 and 1882, at least seven fires were recorded in the community. A Waikato Times Editorial of 18 March 1882 deplored the possible presence of a “fire maniac”. The Oddfellows Hall and Masonic Hotel stables were damaged and Mrs Maxwell’s cottage in Alpha Street was burned to the ground. Mrs Murphy’s Maori restaurant or wharekai near the National Hotel was destroyed by fire, although the occupants believed this was caused by the negligence of neighbouring butcher Thomas Hoy – an accusation he vehemently denied. In a letter to the editor, he implied the fire was caused by the drunken carelessness of the restaurant’s occupants.

In March 1882, local tradespeople funded the appointment of Charles Hassett as a night watchman. Armed with his stick, Hassett was soon a familiar sight to late wayfarers, including the drunks stumbling home from the many Cambridge hotels.

But Hassett wasn’t immune to the pleasure of a drink himself, and had no scruples in frequenting hotels while on duty. According to the Waikato Times, he was twice assaulted – once by bouncer George Walton who threw him outside the National Hotel after he refused to pay; and once by John Arnold after a fracas in the same hotel – Arnold allegedly calling him an “old loafer” for drinking on the job, and Hassett calling Arnold “opprobrious” names and threatening to “pull his nose”.

Perhaps because of this behaviour, the night watchman’s financial support from local tradespeople was dwindling. He had at least one supporter in a Waikato Times correspondent in January 1883, who claimed that Hassett should be commended for foiling an attempt by vagrant James Murphy to burn down George Dickenson’s shop in Duke Street. However, as Murphy had lit only a small fire to warm his billy can, he was released without charge. The Waikato Times reported that “it was generally believed … that if he lit the fire, he did it without any malicious intent, he being somewhat demented.”

It is not clear if Hassett left or was relieved of his post. He was certainly gone by March 1885, when the townsfolk were again requesting that a night watchman be appointed.

Outbreaks

Between 1881 and 1888, at least 32 fires had been recorded in Cambridge, including a major one in November 1883. On Victoria Street, between Queen Street and the Church corner, several businesses were burned to the ground, all being hit with substantial financial loss. The Waikato Times lauded the efforts of the Armed Constabulary, which had controlled the fire by pulling down fences and workshops at its perimeter to keep it from spreading.

Tragedy struck when the three children of William and Mary Osborne died in a house fire near the Waikato river on 6 November 1884. They were Hedley (4 years), Julietta (2 years) and Agnes (5 months). Mrs Osborne had walked to town to buy a suit of clothes for her husband. She had locked the children in the house so that they could not stray down to the river.

An effective water supply for firefighting was yet to be sourced, and the townsfolk were becoming desperate.

Insurance costs

Fire insurance costs in Cambridge were skyrocketing. In 1885, the Borough Council was sufficiently concerned to write a letter of complaint to insurance companies but was told that these costs would continue until the water supply problem was solved.

“FIRE! FIRE!”

According to early resident Mr A Johansen, the main business area of Cambridge at that time was Duke Street. It was originally a sand road, and in the wintertime, he described it as a “veritable bog-hole.” But over time, business increased in the street, bolstered by the money made from participants in Land Court hearings in the town.

On the morning of 9 March 1889, Duke Street residents were awoken by shouts from Edward Cussen and Mr Hadyn, who had seen the reflection of fire in the sky at 3.50am. The blaze had started in Bates’ Saddlery, and the Bates family were lucky to escape with their lives. The school bell was rung as an alarm. The south side of Duke Street East was rapidly becoming an inferno, and residents rushed to the scene to do all they could to save lives and rescue goods and stock. Thankfully, no lives were lost.

The Waikato Times applauded the formidable efforts and level-headedness of the women. Mr Bates was described as “overcome with shock”, while Mrs Bates was praised for her presence of mind in rousing the children and moving them to safety. Miss Ellen Dillon, the cook at the Masonic Hotel, was awakened by the glare of the flames and, with others, went to assist. They “worked like Trojans”, saving an immense amount of goods by gathering it in their skirts and moving it from threatened buildings to safety “in quicker time than the men could have done.”

Aftermath

A photograph taken immediately after the fire shows a sorry site. Businesses affected were:

Bates’ saddlery, Bond’s bookshop, Buckland’s horse bazaar, Cox’s grocery and boot store, Golder’s watchmakers, McNeish’s billiard saloon, Hill’s Melbourne Drapery Company store, Neal’s lime and chaff store, Neal’s seed and flour store, Pierce’s fruitery, Riley’s tailors, Ruge’s barbershop, Sargent’s jeweller and Ward’s chemist.

The south side of Duke Street East was now a smouldering mass of ruins, with chimneys jutting from the ground like charred tree trunks. From that time more and more businesses were established in Victoria Street until it, and not Duke Street, became the main street of Cambridge – effectively turning the town on its axis by 90 degrees.

The Cambridge Fire Brigade

Little progress could be made towards the formation of a Fire Brigade until access to a water supply was secured. So when, in 1903, a water tower was built and water from Moon Creek was pumped to the tank for the town water supply, the people of Cambridge rejoiced.

In May 1904, a special meeting of the Borough Council approved a recommendation to form a volunteer fire brigade, erect a station, and procure the necessary gear. Funds were quickly raised: £60 from townsfolk, with the Council granting £120. The station was erected by voluntary labour, and a hose reel (currently held at the Fire Brigade Museum) produced by local blacksmith John Ferguson. Hydrants and 800 feet of hose were also procured.

The opening of the Fire Brigade was a source of much pride for the town. Speeches, applause and cheers were given, before the firemen gave a short exhibition of hose and reel work that may not have impressed onlookers. According to the newspaper report, “the men have only had the reel a couple of days and have had little or no practice. In time, they will no doubt give a creditable account of themselves.”

The event was held on 24 August 1904, and it was Mayor Thomas Wells who officiated the opening. When he had proposed the formation of a fire brigade back in 1879, little did he know that it would take 25 years to come to pass.

Footnotes

Some of the characters referred to in the previous article have turned up in other research. Here are some more references:

Mrs Murphy

December 1882: Regarding Mrs Murphy’s Maori restaurant or wharekai, the occupants believed that the fire was caused by the negligence of neighbour Thomas Hoy, a local butcher. Hoy was alleged to have left a log fire burning in the back yard of his premises overnight, from whence embers had blown onto the whare. The occupants intended to lay charges.

Thomas Hoy

Mr Hoy wrote a long letter to the Waikato Times claiming that two of his employees had extinguished the fire before he had left that day. He believed that the destruction of the whare had been caused by the wharekai’s “red hot” stovepipe igniting the whare’s roof of tarred canvas. He wrote that, according to public report, the occupants had been “incapable of knowing whether they had extinguished the fire in their stove or not” on the night in question.

July 1884: Thomas Hoy was charged with riding his horse on the footpath in Victoria Street. He and his two friends said that the road there was so bad that they had had no choice. They were charged and fined.

John Arnold

May 1882: Local butcher John Arnold charged Thomas Hoy with sheep stealing. Mr J S Buckland, however, testified that Hoy had earlier bought sheep from him with the same markings as those Buckland had also sold to Arnold. The case was dismissed.

August 1883: John Arnold charged Thomas Hoy with pig trespass. Hoy was ordered to pay costs.

George Walton

8 January 1877: Twenty-eight fallow deer arrived in the country and were introduced to Maungakawa. They came from Burghley Park, the seat of the Marquis of Exeter, England. They arrived on the ship “Thurland Castle” and were under the charge of one George Walton.

January 1883: George Walton wrote an angry letter to the paper, criticising the behaviour of Justices Col. Lyon and Thomas Wells JP at his assault hearing against Mr Hassett, night watchman. Walton claimed that the Justices had been impatient to leave and, after reluctantly hearing only the side of the plaintiff, dismissed the case as “frivolous”. Watson was ordered to pay for a lawyer and two witnesses. His crime, he wrote, was to order a man out of a hotel who had refused to pay for his drink after he had got it.

Researched and written by Karen Payne

First published in the CHS Newsletter, July 2020